10 Legendary Businesswomen Who Made American History

Swyft Filings is committed to providing accurate, reliable information to help you make informed decisions for your business. That's why our content is written and edited by professional editors, writers, and subject matter experts. Learn more about how Swyft Filings works, our editorial team and standards, what our customers think of us, and more on our trust page.

Swyft Filings is committed to providing accurate, reliable information to help you make informed decisions for your business. That's why our content is written and edited by professional editors, writers, and subject matter experts. Learn more about how Swyft Filings works, our editorial team and standards, what our customers think of us, and more on our trust page.

Women in business are not just a hallmark of the modern era. Women have been leaders in the workforce for millennia. They've paved the way for other women through their successes and have acted as role models for future generations. Their stories are not often told, but it's time for their contributions to be known to future business leaders.

In honor of Women's History Month, here are 10 women who broke glass ceilings in the U.S.

Mary Katharine Goddard, Revolutionary War Publisher (1738-1816)

Mary Katharine Goddard was a printer, publisher, and postmaster in the days of early America. She began her career in Providence, RI, publishing for her brother William Goddard's weekly newspaper, The Providence Gazette.

Mary remained publisher of the Gazette after William moved to Philadelphia to publish The Pennsylvania Chronicle in 1765. She joined him in Philly in 1768. While The Chronicle ran in his name, Mary Katharine herself managed the print shop and acted as publisher.

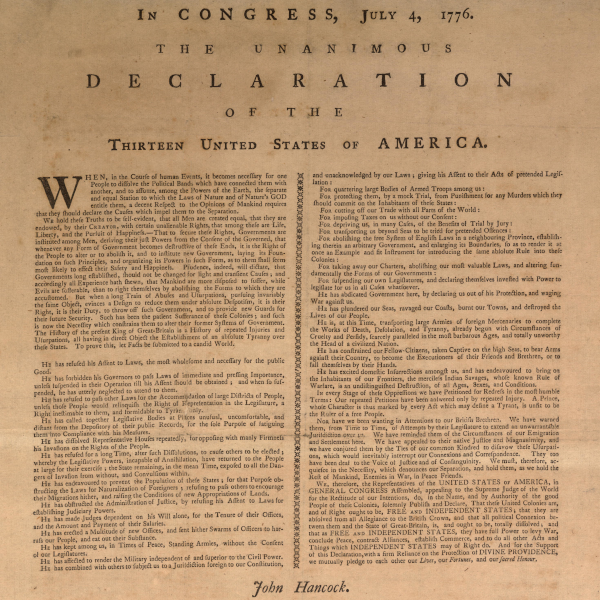

In 1774, Mary moved to Baltimore, where William had set up a new shop printing The Maryland Journal & Baltimore Advertiser, Maryland's first newspaper. Under the name M.K. Goddard, Mary was listed as the publisher starting in 1775, and she managed and edited the newspaper through the Revolutionary War. In 1777, her print shop published the first printing of the Declaration of Independence with the names of all signers.

In 1775, Mary Katharine Goddard became Baltimore's postmaster, a position she held for 14 years. Postmaster General Samuel Osgood removed her from the job in 1789, to the general public's dismay and outcry, claiming that new duties that included a great deal of travel would be too strenuous for a woman to fulfill.

After her removal as postmaster, Goddard operated a bookstore until 1809 or 1810. Before her death in 1816, Goddard freed her single slave, Belinda, and bequeathed her all her possessions and property.

Rebecca Lukens, America's First Female Industrialist (1794-1854)

Early American industrial tycoon Rebecca Lukens is sometimes named America's first female industrialist. Her father, Isaac Pennock, founded Federal Slitting Mill, an ironworks company, in 1793. Through her early life, Lukens learned the family business. After her education, she met and married Dr. Charles Lloyd Lukens in 1813.

Lukens convinced her husband to leave the medical profession and join her father in the iron business. Under Dr. Lukens' advice, the company was rebranded as Brandywine Iron Works and became the first company in the U.S. to produce the boilerplates necessary for steam engines.

In 1825, Lukens' husband died, passing the business to her. Lukens became a shrewd business manager and eventually completely rebuilt the mill. Under her leadership, the business survived and remained profitable through several economic downturns. Thanks to Rebecca Lukens, Brandywine Iron Works became the longest continuously-run iron and steel mill in the U.S.

Mary Ellen Pleasant, Real Estate Tycoon and Mother of Civil Rights (1814-1904)

Philanthropist, real estate tycoon, and investor Mary Ellen Pleasant was known as the mother of civil rights in California. Born a slave, Pleasant was a very light-skinned Black woman. When her freedom was purchased at an early age, she began working as a conductor on the Underground Railroad, helping others escape slavery.

Pleasant moved to San Francisco during the Gold Rush in 1852, where she passed as a white woman and worked as a cook in men's eating houses. Many patrons were wealthy city leaders, and she picked up valuable investment information by eavesdropping on their conversations. She invested her money and opened restaurants, laundries, and boarding houses. By 1865, she had amassed a fortune.

Though she passed as white in many circles for years, she was openly Black to the city's African-American community. Known as "Black City Hall," Pleasant used her many connections to help Black people and newly-freed slaves get opportunities and jobs. Pleasant used her power and wealth to help Black people across the country and remained an advocate for abolition and civil rights throughout her life.

Pleasant helped establish a town in Canada as a new home for freed slaves and donated $30,000 to fund abolitionist John Brown's slave revolt at Harpers Ferry. When Brown was executed after the failed revolt, a note was found in his pocket. It read, "The ax is laid at the foot of the tree. When the first blow is struck, there will be more money to help."

The note was signed "MEP." Fortunately for Mary Ellen Pleasant, officials misread the initials as "WEP," keeping her involvement out of the record.

Elizabeth Hobbs Keckley, Former Slave Turned Elite Seamstress (1818-1907)

Elizabeth Hobbs Keckley was born a slave in Virginia, daughter of Abby and George Hobbs, though her biological father was her slave owner, Colonel Armistead Burwell. Her mother sewed clothes for the Burwells and taught Keckley her trade at the age of five.

Keckley worked for the Burwells for years in Virginia, North Carolina, and St. Louis. In 1855, she purchased her and her son's freedom, using funds from her dressmaking and the aid of patrons. She soon moved to Washington D.C. to pursue a seamstress business. Her enterprise grew to employ 20 seamstresses.

Keckley's business thrived in D.C., creating dresses for prominent politicians' wives, including those of Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee. Her most famous client was First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln, and Keckley became her personal modiste and dresser as well as a close personal friend. They continued their relationship for years, through the deaths of both of their sons and the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.

Keckley published her autobiography "Behind the Scenes: Or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House" in 1868 to some controversy, which soured the friendship between her and Mary Todd Lincoln. Keckley passed away in May 1907 at the age of 89.

Lydia Estes Pinkham, Inventor and Women's Health Advocate (1819-1883)

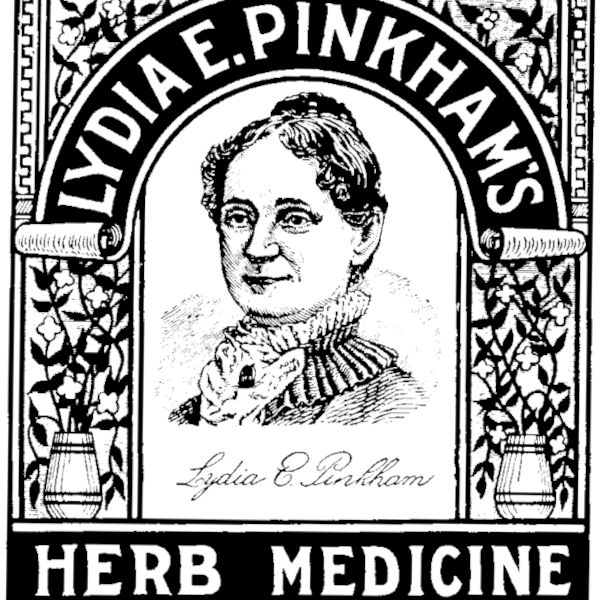

Dissatisfied by male physicians and the poor quality of gynecological health products, Lydia Estes Pinkham started selling Lydia Pinkham's Vegetable Compound, an herbal medicine to relieve menstrual discomfort and menopausal symptoms, from her home kitchen in 1873. She initially shared her products with friends, but word of mouth quickly spread, and she began getting requests for her medicine from strangers.

Pinkham received a patent for her compound in 1876. With the help of her sons, she established Mrs. Lydia Pinkham's Medicine Company to mass-produce her product. She turned her home basement into a factory, bottled and packaged the medicine at home, and distributed advertising pamphlets throughout her neighborhood and town. Pinkham was soon selling her product across the U.S.

With her face prominently printed on advertising and bottles of her medicine, Pinkham became the matronly mascot of gynecological health throughout the country. She received letters from her customers on a variety of health issues and published pamphlets under her established Department of Advice, staffed by women only. She continued to publish reproductive health publications throughout her life.

Madam C.J. Walker, America's First Self-Made Female Millionaire (1867-1919)

America's first self-made female millionaire was the legendary Madam C.J. Walker, Black women's hair care specialist.

Born Sarah Breedlove in 1867 to sharecropper parents, Walker was the first of her family born free. She was orphaned at six, married at fourteen, and widowed at twenty. In 1889, Walker moved to St. Louis to live with her three brothers.

Inspired to create Black women's hair care products after losing much of her hair to a scalp condition, Walker began to learn about hair and scalp health through her brothers, who owned a barbershop. Armed with her new knowledge and with the help of wholesale druggist Edmund L. Scholtz, she began developing an ointment to heal scalp disease.

Walker sold her homemade products directly to Black women, door to door. Many Black women's hair care products at the time were marketed and sold by white companies and were ineffectual for Black women's health and beauty. She eventually expanded her sales line by employing saleswomen called "beauty culturalists" through multi-level marketing sales.

In 1905, Walker moved to Denver, and her products began to sell quickly. She married Charles J. Walker in 1906 and changed her name to Madam C. J. Walker, a name that she began using on her products along with a photo of her face, in much the same fashion as Lydia E. Pinkham. The Walkers traveled from Denver through the south to market and sell her products, growing the business further.

Walker chose Pittsburgh as the temporary home base of her growing business. There, she set up a beauty school and factory. Later, she moved her operations to Indianapolis. Her customer base continued to expand nationwide.

Walker opened beauty schools and factories for her products throughout her life, producing shampoos, cold creams, and hot combs, amassing a fortune. In 2020 Netflix released a limited series starring Octavia Butler called "Self Made: Inspired by the Life of Madam C.J. Walker."

Elizabeth Arden, Cosmetics Empress (1881-1966)

Florence Nightingale Graham, better known as Elizabeth Arden, was a 20th-century beauty tycoon. Through her business operations, Arden was the first to market makeup and cosmetics as a respectable industry, suitable for middle and upper-class ladies rather than just for performers or sex workers.

Arden began her career bookkeeping for a pharmaceutical company in Manhattan after dropping out of nursing school. By 1908, Arden was working as assistant to beautician Eleanor Adair and started spending long hours in the labs learning about skincare. Two years later, armed with valuable industry knowledge, Arden opened her own salon on Fifth Avenue.

Arden expanded her business internationally in 1915. She opened salons and spas in Paris, Italy, and across the globe. She introduced makeovers as part of her marketing and personally opened every salon under her name.

Arden was active in the fight for women's votes, supplying suffragettes with red lipstick as a symbol of strength. During the Great Depression, her business continued to thrive. She remained the primary owner of her company until her death, making her one of the richest and most well-known women of the 20th century.

Olive Ann Beech, First Lady of Aviation (1903-1993)

Known as the "First Lady of Aviation," Olive Ann Beech, born as Olive Ann Mellor, always had an aptitude for business and finances. She had her own bank account at age seven and ran her family's finances from age 11.

In 1924, at age 21, Beech became a bookkeeper and office secretary at Travel Air Manufacturing Company. She quickly rose up the ranks and became office manager and personal secretary to founder Walter Beech. They married in 1930 and moved to New York.

In 1932, the Beeches founded Beech Aircraft Company. Olive worked the business's financial side and was a decision-maker in the company's airplane production. When her husband became gravely ill in 1940, Olive took over company leadership. She helped produce aircraft for the U.S. during World War II and later assisted NASA in space exploration technology.

In 1980, Beech was awarded the Wright Brothers Memorial Trophy, the highest honor in aviation, for contributions to the aircraft industry. She earned more awards and citations than any woman in aviation history.

Estée Lauder, Beauty Icon (1906-2004)

Another visionary beauty icon, Estée Lauder (née Josephine Esther Mentzer), established her eponymous beauty empire and became one of the most influential business owners of the 20th century.

Lauder began her interest in cosmetics early in life. As a young woman, she aided her chemist uncle in creating skincare products and fragrances. In 1930, Lauder married Joseph Lauter, who later changed their surname to Lauder. He helped her sell her cosmetics through beauty salons.

After years of selling products personally, Lauder established Estée Lauder Cosmetics Inc. in 1946. With the release of her first perfume, Youth Dew, in 1953, Lauder changed the fragrance industry forever. She wanted a scent that women felt comfortable buying for themselves and using every day, rather than waiting for their husbands to gift them with a perfume for special occasions.

Lauder's genius for business included several marketing and sales techniques, including the "gift with purchase" practice that became industry standard. She focused on personal customer service, insisting that her sales agents apply products to customers' faces to demonstrate their effectiveness.

Lauder took a high level of interest in her stores' day-to-day operations, attending the openings of nearly every store and advising on customer service and display techniques. When Time magazine published its list of the 20 most influential business geniuses of the 20th century in 1998, Lauder was the only woman on the list.

Katharine Graham, Newspaper Magnate and First Female Fortune 500 CEO (1917-2001)

Katherine Graham, born Katharine Meyer, was an American publisher who owned and published various newspapers, including The Washington Post.

Graham began her career writing as a reporter for San Francisco News in 1938. A year later, she joined the editorial team at The Washington Post, a newspaper purchased by her father in 1933. She married Philip Graham in 1940, and her father gave ownership of the paper to her husband.

Following her husband's suicide in 1963, Graham assumed ownership of the Post. Under her direction, the paper became known for its hard-hitting investigative journalism. Following groundbreaking coverage of the Watergate scandal in the 1970s, the Post soon became one of the most widely-read and influential papers in the nation.

As chief executive officer of the Washington Post Company, Graham became the first female Fortune 500 CEO. She won a Pulitzer Prize for her memoir "Personal History," published in 1997.

Legacy in Business

Each of the women above has made a lasting impact on the future of women in the workforce. Through their leadership and their breaking down of gender barriers, they each paved the way for the next generation of female entrepreneurs.

More women are now starting businesses than ever before in American history. In the past two decades, the number of women entrepreneurs has increased 114%, according to a 2019 study by American Express. In 1972, only 4.6% of all businesses in the U.S. were women-owned, but that number had increased to 42% by 2019.

There is still a lot of work to do for true equality in the workplace. On average, women are still being paid less than men for their work, just 82 cents for every dollar earned by men, according to Census Bureau data in 2018. The wage gap is even more significant for women of color. However, women of color, on average, start more businesses than their white counterparts and are seizing control of their own wages and profit as a result.

The women in this article may have had a tough time, but they overcame the odds and became success stories that every woman entrepreneur can look to for guidance. They've proved that through hard work and dedication, glass ceilings are nothing to fear for businesswomen today. The sky is the limit, and the future is bright.

Want to Learn More?

To learn what you can do to support trailblazing women entrepreneurs today, check out How to Show Your Support for Women-Owned Small Businesses. Already have a business and want to get certified? Check out How to Get Certified as a Women-Owned Business. For business tips and entrepreneurial advice, try 5 Tips on How to Be a Successful Female Entrepreneur.

Swyft Blog

Everything you need to know about starting your business.

Each and every one of our customers is assigned a personal Business Specialist. You have their direct phone number and email. Have questions? Just call your personal Business Specialist. No need to wait in a pool of phone calls.